Edit: This has been restructured and rewritten a bit to make the post come off a bit less personally, since that wasn’t the intention.

Groovy Superhero is running a series on The World’s Fastest Cancellation, looking at the way the series has been relaunched over and over since Geoff Johns 2005. The Flash has had a remarkably consistent writing credit over the years, until Geoff Johns left the book in 2005 to do Infinite Crisis.

Wally Before Geoff

One thing the author of that series said got me thinking about the series’ creative history: In part one, he or she writes about the book after Geoff Johns left it:

The Flash…was relegated to the status he had endured throughout most of the ’90s: a “who needs work?” book, being tossed around from creator to creator

Tossed around from creator to creator? True of the last three years, but certainly not true of the 1990s. William Messner-Loebs wrote the book for four years from 1988–1992. Mark Waid* took over in 1992 and stayed on until 2000 (Brian Augustyn joining him officially halfway through after several years as editor and an uncredited co-writer), with a one-year break during which he wrote JLA: Year One and Grant Morrison and Mark Millar filled in. In fact, if you count the Morrison/Millar run as a main creative team, there’s a grand total of only five issues by fill-in writers** from #1 to #225 (the end of Geoff Johns’ run), covering 1987–2005.

Long-Term Consistency

If you go further back, Gardner Fox wrote most of the Golden Age books, with Robert Kanigher coming in near the end. John Broome wrote most of the Silver Age, with Fox and Kanigher. There was a transition period in the late 1960s, and then Cary Bates wrote nearly every issue from the early 1970s through 1985.

Three main writers from 1940-1970. One from 1970-1985. Five writers or writing teams from 1987-2005. (I’m lumping the Waid/Augustyn and Waid solo runs together. Same with the Morrison/Millar and Millar solo books.)

Now let’s look at the book after Geoff Johns left in 2005:

4 issues by Joey Cavalieri

8 by Danny Bilson & Paul De Meo

5 by Marc Guggenheim

7 by Mark Waid

6 by Tom Peyer

4 by Alan Burnett

2 one-shots

Six writing teams in three years, and a couple of one-offs.

Flash or Thrash?

Following Johns’ final issue, it’s clear they had already decided to axe the book, since all that remained was one stand-alone story that had been sitting on the shelf and the 4-part “Finish Line,” which was clearly intended (like the current “This Was Your Life, Wally West”) to wrap up the series.

Then DC proceeded to throw lead characters, creative teams, and creative directions at the wall haphazardly, hoping something would stick. How could anything gain traction with that much churn?

In my opinion, given that DC is already committed to relaunching the series with Flash: Rebirth, the best thing DC could do to build the book back up would be to keep Geoff Johns on after the miniseries, and give him at least a year to establish the series tone, direction, and at least one long-term arc. Then make sure that whoever follows him is sufficiently high-profile not to scare readers off, and won’t simply throw everything out and start over.

Notes

*By part 5, he explains that “Waid’s main contributions to the Flash mythos were to introduce Wall and Wife Linda’s twins.” Now, I would assume that he meant Waid’s contributions this time around, but given the remark in part 1 about the series being a dumping ground of random writers in the 1990s, I have to wonder whether the writer in question is simply not familiar with Waid’s eight-year run, or that it established the Wally/Linda relationship, introduced the Speed Force, built up a family of speedsters, spun off an Impulse/Max Mercury book, and really established the Flash as once again being a major player after 60-odd issues of the B-list.

**Those fill-ins would be:

#29: Len Strazewski (1989)

#151: Joe Casey (1999)

#160: Brian Augustyn solo, not sure you can properly call it a fill-in. (2000)

#161: Pat McGreal (2000)

#163: Pat McGreal (2000)

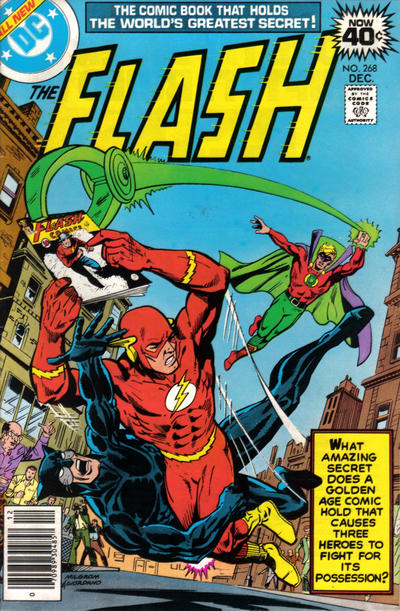

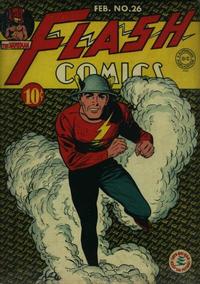

The first Flash comic I remember purchasing was Flash #268. If you just look at the cover, you will discover three characters fighting over a Golden Age comic, Flash Comics #26. The cover blurbs state that this is “the comic book that holds the world’s greatest secret!” In the bottom left corner, the cover asks the question, “What amazing secret does a golden age comic hold that causes three heroes to fight for its possession?”

The first Flash comic I remember purchasing was Flash #268. If you just look at the cover, you will discover three characters fighting over a Golden Age comic, Flash Comics #26. The cover blurbs state that this is “the comic book that holds the world’s greatest secret!” In the bottom left corner, the cover asks the question, “What amazing secret does a golden age comic hold that causes three heroes to fight for its possession?”  Writer Cary Bates is responsible for the entire Bronze Age of the Flash, but has been missing from the DC Universe since the early 1990s.

Writer Cary Bates is responsible for the entire Bronze Age of the Flash, but has been missing from the DC Universe since the early 1990s.